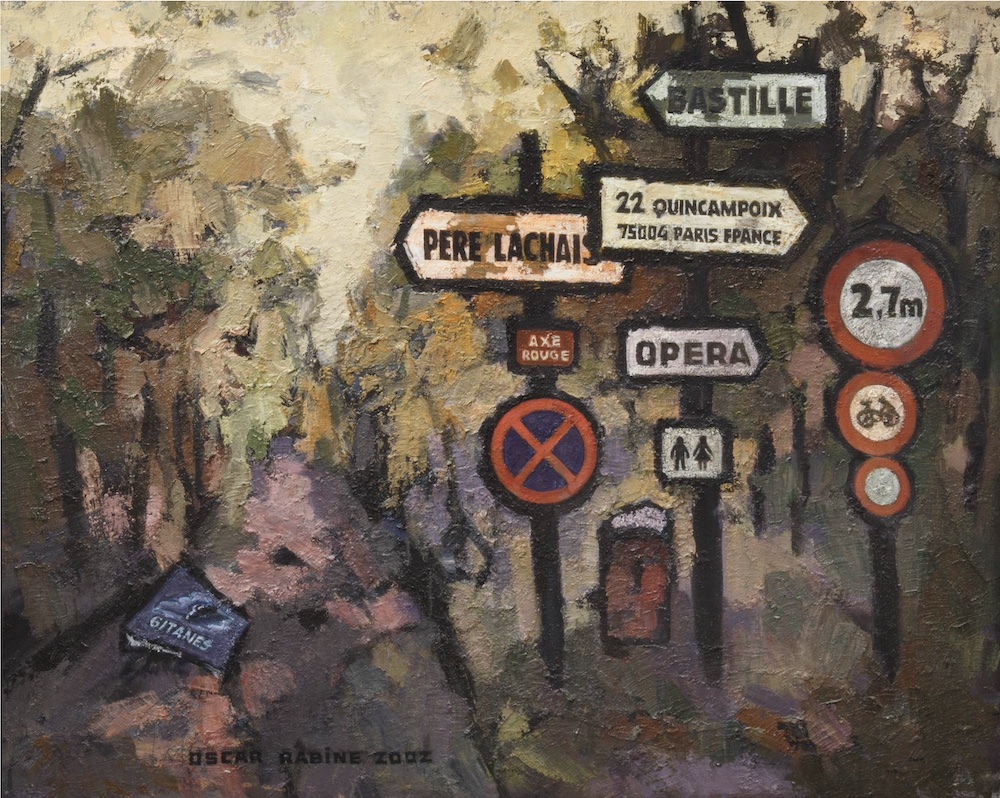

Description

Oscar Rabin (1928 Moscow – 2018 Florence)

“Road Signs in the Bois de Vincennes”

Material: Oil on canvas

Dimension: 65 x 81 cm

Frame: Yes

Date: 2002

About the Artist:

Oscar Rabin (Russian: Оскар Яковлевич Рабин; Moscow, 2 January 1928 – Florence, 7 November 2018) was a major Russian painter and activist who defined the core of the Soviet Nonconformist Art movement, affecting the careers of countless painters and sculptors of that era and its aftermath.

An artist’s preference for a tradition becomes determined first of all by that artist’s personal likings, but the concept of school too is very important in the formation of an individual style. Although incomplete, Rabin’s training was in the classic mould, first at the Riga Academy of Arts (1944-1947) and then at Moscow’s Surikov Institute (1948-1949).

Rabin belongs to the generation whose adolescence and youth coincided with the troubled years of World War II. His contemporaries include artists, who were exponents of several differently-oriented trends formed in the post-war period and symbolized for a majority of intellectuals the uproarious years of Khrushchev’s “Thaw”. In the West the art of the second half of the 20th century is normally called post-war art, which probably most aptly reflects the essence of the world outlook of the many artists whose art was taking shape in the 1950s-1960s.

Rabin’s book “Three Lives” narrates the tragic events of the war period, the experience of losing parents, homeless wanderings, post-war life of penury, hunger, desperation, and attempts at suicide. Rabin’s literary style is marked by the same intonations as his pictorial imagery. The author does not force empathy on the reader, but seems to be watching himself as if from outside. This angle of view deepens the reader’s awareness of the horror and absurdity of the experience. Such distancing from reality in the depiction of most ordinary objects and events became one of the signature features of the artistic language created by the artist.

Lamps, barracks, fish, postage stamps, labels, coins, passports — all these things that make up human environment are elevated by Rabin to the plane of self-contained iconographic narratives barely fitting the confines of any single genre. “Three Roofs” (1963) stands out as one of the best urbanistic antipoles of socialist realist industrial landscape, a group of “antithetic” works to which “City with Fish”, “Night”, “Bottles, Barracks and Crane No. 2” (Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, New Jersey) can be said to belong to. “Moon and Skull” (1973) elaborates on the theme of “vanitas” — the never-fading theme of the changeability and futility of existence, which dates back to Rabin’s early pieces. The pictorial representation of the “memento mori” thesis reaches here a nearly ostentatious symbolism reflected even in the title itself. The propensity to turn artwork into symbols and, conversely, to make a certain set of material trappings of human existence, such as postage stamps, road signs and documents, into artwork gave rise to the pop-art works, including the picture “One Ruble” (1967). A special medium used by Rabin — a mixture of oil paint and sand — lends volume to his images, making them nearly palpable.

The maestro’s personal credo was formed in a fellowship of artists known as the Lianozovo school, although that was not a school in the traditional meaning. And yet Rabin better than anyone could accumulate in his art the common, barely perceptible intonation shared by the poets and artists of the Lianozovo circle. The idea that the Lianozovo group was an association of like-minded artists is true mostly in the context of the ties of friendship and in-law kinship and the community of worldviews shared by the artists and poets gathered around Yevgeny Kropivnitsky.

Rabin and Kropivnitsky first met during the war, when Rabin, a teenager who was not evacuated because of his mother’s illness and became an orphan soon after, decided to enroll at an art workshop. “…I saw an announcement that an art workshop was opened at the Young Pioneers Club. I went there. I learned that the workshop was directed by Yevgeny Leonidovich Kropivnitsky and only three children enrolled. The poetry workshop, also directed by Yevgeny Leonidovich, also had only three enrollees.” According to the poet Vsevolod Nekrasov, the Lianozovo group, which emerged later from this close circle of kindred spirits, “was not a group or a manifesto but a household arrangement. Although ultimately the participating artists shared something in common in their artwork as well.”

This artistic alliance can be better characterized precisely from the viewpoint of a community of themes and poetic language. For the artists and poets alike, it was a circle of friends and relatives. At first the meetings took place in the home of Kropivnitsky and his wife the artist Olga Ananievna Potapova, and later, in Oscar Rabin’s home in a converted labour camp barracks close to the Lianozovo railway station, where he settled together with Valentina Kropivnitskaya (the daughter of Kropivnitsky and Potapova). Their home was frequented by Nikolai Vechtomov, Lidya Masterkova, Vladimir Nemukhin, and Lev Kropivnitsky, Yevgeny Leonidovich’s son who returned from the war in 1945 and was sent to the Gulag in 1946.

Oscar Rabin was the only one to develop an individual style blending together a poetic narrative and pointed expressiveness characteristic of the Lianozovo artists and poets.

Just like the Lianozovo poets, Rabin has always said that he depicts what he sees around him. “I depict what I see. I lived in a barrack — many Soviet people lived in barracks, many live in them even now … Recently I moved to a standard apartment block and now portray the neighborhoods consisting of apartment blocks around me.” The phrase “I see” is perhaps the key in this statement. The artist can see the most ordinary household objects through a very special lens.

A technique of adding a meaning to the things seen, which Rabin used when he was still Kropivnitsky’s student and which he later modified, became a feature of his special style. In the mature works such as “Vladimir Nemukhin’s Samovar” (1964) and “Glezer’s Primus” (1968) this style was brought to perfection. The artist does not create portraits of his friends or ordinary still-lifes. In Rabin’s works, the self-portraits and people’s images are only an accessory evidence of their existence, captured in photographs and documents or imprinted on postage stamps, playing cards and road signs. The hardships of post-war homeless wanderings were impressed on Rabin’s mind as recollections of a world with certain conventions, a world where a document can be more important than the person, and in order to escape obliteration from the face of the earth, one has to authenticate one’s existence with a passport. The strength of this “conditional” unfreedom is such that you need a visa even to a graveyard. Although Rabin’s works are free from ostentatious social criticism typical of invective, they were often perceived by his contemporaries as a slander against reality, or were seen as a social protest, which was to some extent one of the rules in the fine tug-of-war between the artists and the authorities.

On his way to an individual style, Rabin reached a crucial junction when he wanted to participate in an exhibition held at the International Youth Festival in 1957. The artist’s works were rejected at a first round of selection, and at a second round as well, but provoked a lively reaction among the jurors. Finally only one Rabin’s pieces was selected for the show — a picture of a modest bunch of field flowers, executed in the little known technique of mono-typing.

The artist was rewarded for the piece with an honorary diploma, which soon enabled him to quit a hard job as a foreman at the Severnaya waterworks and find a job at a design workshop already employing Nikolai Vechtomov, Vladimir Nemukhin and Lev Kropivnitsky. For the first time in his life Rabin had a chance to earn his living with a brush and a pencil and to actively participate in the ebullient cultural activities of the artists. That was during the most politically relaxed period of Khrushchev’s “Thaw”.

A desire to secure a wider audience than the small circle of associates and fans, and not just for himself but for kindred artists as well, made Rabin open the door of his barracks to every member of the interested public in 1958. Informal recognition (the “reception days” in Lianozovo were a huge success) was replaced by the wrath of officialdom. In 1960 the “Moscovsky Komsomolets” newspaper ran an article by R. Karpel “Priests of the scrap yard No. 8.” In 1974 the exhibition — later known as “Bulldozer exhibition” — organized by Rabin ended up in a scandal. The authorities’ attempt to tame such inconvenient artists forced many of them to leave Russia.

In 1978 the artist together with his family went to France on a tourist visa. That journey turned into an enforced exile. Six months later Rabin was stripped of his Soviet citizenship, and it was not until 2006 that he was issued a Russian passport.

In France Rabin created a series of iconographic works that were conceived while still in Russia but have a different emotional tonality. “The Russia-themed pictures that I sometimes paint even now are not nostalgic. These are pictures-cum-recollections — just a memory about the past. For no matter what sort of past it was, you cannot erase it from your heart.”

The main visual components in Rabin’s artwork are shaped in line with the principles of expressionist aesthetics. His art within the context of post-modernism appears as a rare version of post-expressionism, one which emphasizes not just a manifesto of subjectivism but also its objectification. His subjective vision can afford to an attentive viewer a glimpse of the world of scores of people living after World War II, who, although having survived, seemed to have gone out of existence, located outside the boundaries of the allowed reality.

Oscar Rabin’s works occupied a well-deserved place in the rooms of the Krymsky Val halls of the Tretyakov Gallery, where a new exhibition of 20th-century art was installed in 2007. A display of the nonconformist artist’s works side by side with the paintings of the Soviet masters approved by officialdom is bound to convince the audiences that Rabin’s art is a part of the cultural legacy of 20th-century Russian art, a fragment without which any objective picture of the time would be incomplete.